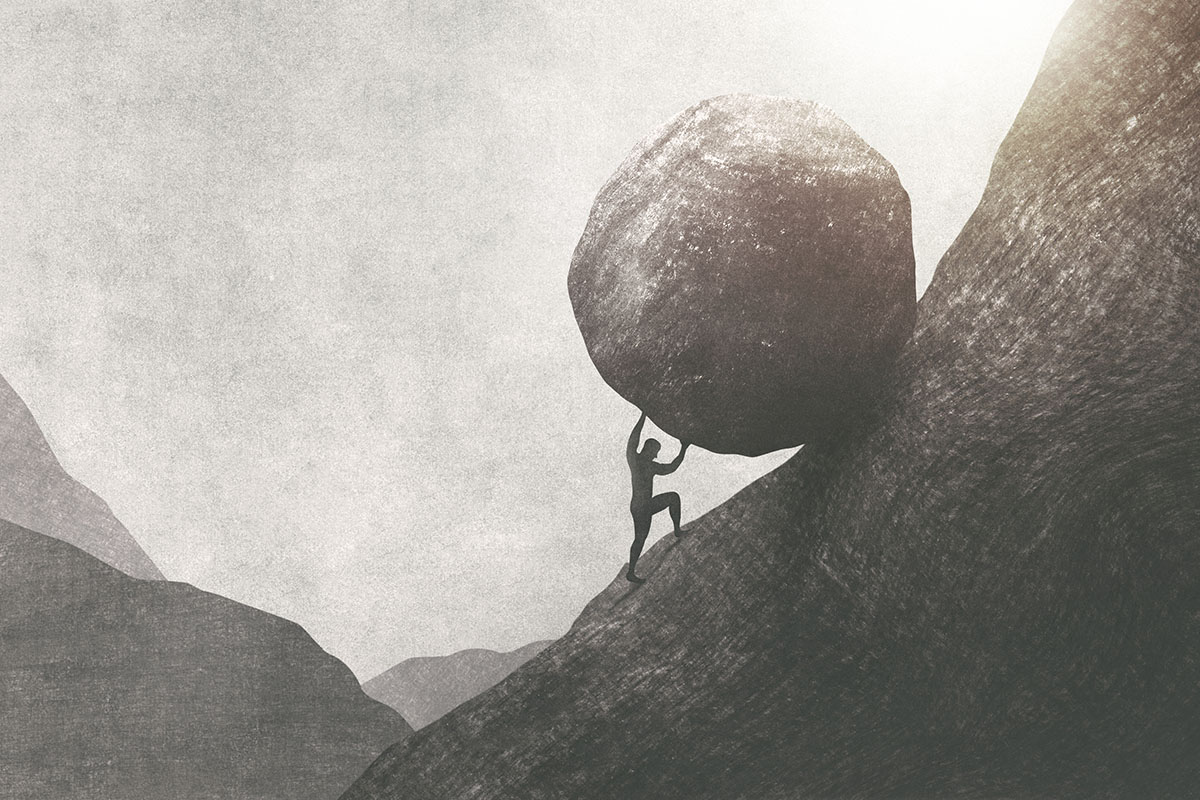

Don't wait for things to get easy

Posted 11/1/2022

“You’re probably overwhelmed right now, but next year may feel even tougher.” I had just started as a professor, and almost spit out the coffee I had been enjoying with my well-meaning colleague. Seventeen years later, that remark is my only memory from our hour-long conversation. It was shocking, perceptive, and ultimately reassuring.

My colleague knew I expected to be overwhelmed in year one as I learned my new job. He also knew that I might get discouraged when time passed but the feeling remained as new and different hurdles arose. It was never going to get easy. The proper response was, therefore, not to bide my time until the struggles dissipated, but rather to learn to navigate continual challenges and growth. After acknowledging that learning the job was not a temporary hurdle, I quit trying to push through until I “knew what I was doing.” Instead, I focused on finding a healthier pace of stress and growth, and on learning processes for responding to new challenges.

Getting hired to a faculty position and going through a tenure review might appear as singular milestones interspersed between more static work periods. A closer look at any specific career, however, will reveal a continual progress of struggle and advancement. Just getting to the start of a faculty job requires building vision and expertise through a series of undergraduate and graduate education experiences. And once you embark on your faculty career, each success will generate more challenges: invitations to speak at meetings, join journal editorial boards, lead larger research projects, and serve on committees. Your stresses as a student evolve as you grow from a novice needing considerable supervision into a more independent scholar. Similarly, your stresses as a new faculty member should evolve from learning the basics of teaching and advising into more advanced management tasks.

Navigating continual challenges requires two things: learning to solve new problems, and learning to be comfortable with your lack of mastery.

To learn to solve new problems, find mentors who can share insights and guidance. When learning to write proposals, ask senior colleagues for copies of their old proposals, or work with them on a collaborative proposal, so you can observe their process. When teaching a class for the first time, ask other instructors for copies of their notes. Ask lots of questions about how people approach various tasks and situations, filtering their answers to find the ones that work for you. As your career advances, keep finding people ahead of you who can help you navigate your latest task. If you stay quiet out of fear that your questions will be met with disapproval, you’ll miss out on invaluable resources and insights. Not everyone will be forthcoming, but over time you’ll identify supportive allies and save yourself tremendous time and frustration. This support won’t eliminate the hard work of developing your scholarship, but it can help avoid detours and reduce procedural overhead.

To be at peace with your lack of mastery, commiserate with peers. Mutual silence reinforces the feeling that everyone else knows what they are doing, but vulnerable conversations can reveal that struggles are universal. Obviously, nobody starts the job knowing how to advise students, write proposals, and juggle dozens of new obligations! It will be helpful to hear this confirmed by others. The best peers for this are those who understand what you’re going through but aren’t responsible for evaluating you. As one successful young professor told me, "Some of my junior colleagues don’t want to share that they have any problems, so it’s been essential to connect with pre-tenure professors at other institutions."

Another way to manage your lack of

mastery is to make mental space for celebrations, and stay aware that

you are competent and making progress. Big milestones like tenure are

rare, and offer only temporary fulfillment. So be mindful about

constantly spotting small victories. Did you have an insight into how to

explain a difficult concept in class? Did an advisee make progress with

their work? Was somebody engaged and nodding while you gave a seminar?

Notice and enjoy those successes as an end in themselves, rather than

waiting for grand milestones. A daily gratitude journal or a “done list”

are structured ways to stay conscious of your progress.

I’m now deep in my second decade as a faculty member. I am currently challenged by a new administrative job, starting as editor-in-chief of a journal, new research problems, and more. I mostly relish these as opportunities to learn new skills, rather than potential evidence that I am not up to the job. If I had retained my initial perspective of assuming I would know everything after my first year, my colleague could easily have said, “year 17 may be even tougher.”

Sign up for very occasional updates about new offerings.