The peer-review process

Introduction

You’ve completed your research, written your manuscript, and are ready to submit it to a journal! There are still several steps remaining before you have officially published a peer-reviewed paper. This process is opaque to many young scholars, but some basic knowledge will help you navigate it more effectively. This article is aimed primarily at authors who have never published a paper before, but slightly more experienced students may also learn a few things.

Peer review is the foundation of scholarly publication. Research requires specialized knowledge, so the opinions of other experts in the field are used to evaluate whether a manuscript is novel and has conclusions supported by the presented results. By rejecting low-quality or misleading work, a journal builds a reputation as a reliable source of information. And when authors know that their work will be closely scrutinized, it encourages them to be careful with their work and writing. This quality control is important because knowledge is cumulative, and others will cite published work as justification for particular concepts or methods. The process is not perfect–flawed papers are accepted all the time, and peer review is not designed to detect outright fraud. But despite its limitations, peer-review is an important element of scholarly research.

My description below is based on my experience as an author, reviewer, Associate Editor, and Editor for a number of engineering and science journals. Procedures and norms vary somewhat from discipline to discipline and journal to journal, but most of this content should be broadly accurate.

Steps in the process

The main steps of the review process are listed below and discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Submit to the journal

Journal processing

Decision

Revise and resubmit

Post-acceptance processing

Submit to the journal

You will first submit your manuscript to an online system. If the journal allows it, I suggest that you post a preprint first. You will submit several items, and those items vary by journal, so log into the submission system ahead of time to determine which items you need to prepare. Common items you will be asked for are:

Your manuscript. Usually, you will submit a single PDF file with all figures and tables included. The journal will specify how they want the document formatted, such as the reference style and the maximum allowable length. Some journals provide Latex or Word templates, which makes compliance easier.

A cover letter. Start with something simple like the following, and explain any unique issues with the manuscript.

Dear Editor,

Please find attached our manuscript entitled “...,” which we request you consider for publication in [journal name]. We confirm that this is original work and has not been submitted elsewhere for publication.

[You can often re-use material from theses, proceedings, or reports that are not widely distributed, but if this is the case, then declare it in the cover letter and explain the degree of overlap. Check the journal’s author guide for what they allow, and discuss with your advisor before submitting.]

Sincerely,

- A pointer to data or code used to produce your manuscript.

- Sometimes, a list of suggested reviewers or reviewers to avoid. You can suggest reviewers that have specific expertise or have recently published in the same area. Browsing the authors of papers you referenced is a good way to find candidates. Junior reviewers tend to be more responsive, and senior reviewers tend to have a broader perspective. Both can be good. If you cover multiple disciplines in your manuscript, think about reviewers from each. Think about who you hope will read the paper and who could give you the best feedback. It’s better to get their input now when you can still address or clarify any issues. If there are scholars you are competing with on the manuscript topic or have had personal difficulties with, it is okay to list them as reviewers to avoid. It can be helpful to provide the reason if you are comfortable doing so, to show the Editor that you are not simply trying to avoid critical but fair reviews.

Contact information for your coauthors (and their Orcid IDs, if they have one). Some journals send an automated confirmation message to your coauthors once you submit, so alert them before you submit. I suggest sending a note to your coauthors when you are ready to submit, saying something to the effect of “I am planning to submit our manuscript in two days, so let me know if you have any final comments before then. Additionally, please send me your Orcid ID and let me know if you have any suggested reviewer ideas.”

A signed copyright form, giving the journal copyright and permission to publish.

[your name]

When you submit your manuscript to the journal, I suggest simultaneously sending it to a few leaders or colleagues interested in the topic, asking for their feedback. Tell them that you just submitted it for review and that if they have any suggestions, you’ll have time to address them during the review process. This is a chance to start disseminating your work, and you can use their feedback when revising the manuscript in response to review comments.

Journal processing

An assistant will first review your manuscript to check for compliance with journal requirements. If your initial submission had any compliance problems, you might get a request for fixes in a few days.

The technical review then begins. The Editor will evaluate whether the manuscript topic matches the journal’s focus and whether the general quality is sufficient that it might get through review. The Editor will also use a plagiarism checker to see if any text was taken from another document (your own or someone else’s). If it fails any of those evaluations, you will hear back with a short statement that the journal has rejected the manuscript. This is called a “desk rejection,” and it can be disappointing, but with careful preparation and careful choice of journal, it should be avoidable most of the time.

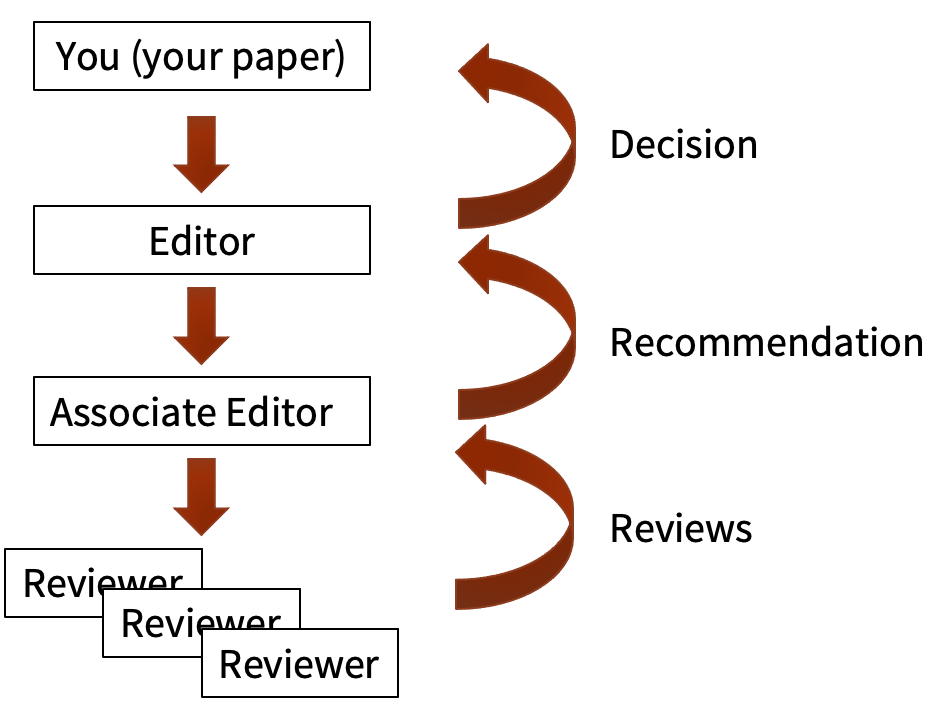

If the manuscript passes the above checks, the Editor will send it on for review. In most journals, the Editor will assign it to an Associate Editor with expertise in your topic. The Associate Editor may immediately recommend rejection based on some fatal flaw that the Editor didn’t identify. Otherwise, they will invite several scholars to review the manuscript and provide feedback. These reviewers are fellow researchers with expertise in your area (your peers–hence the name “peer review”). When inviting reviewers, they will consider the suggestions you provided, authors of papers you cited, experts they know of, keyword searches within the journal’s reviewer database, and other sources. They are not obligated to use your suggested reviewers, but your suggestions may assist them in identifying qualified reviewers.

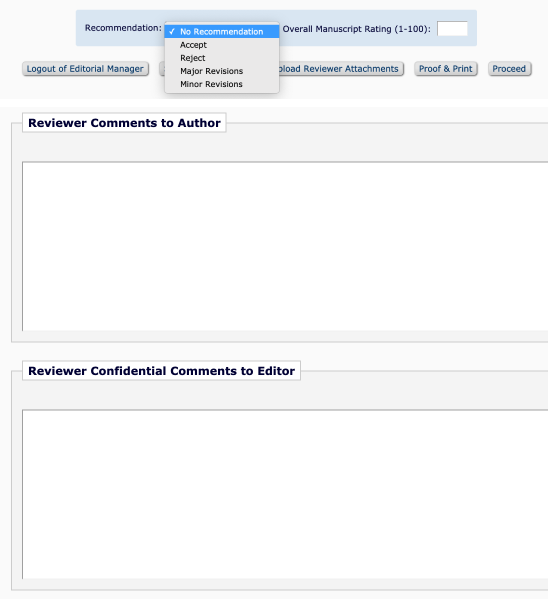

The reviewers will provide reviews back to the Associate Editor, consisting of three parts:

A recommended decision.

A review for the author.

Confidential remarks for the Editor. Most reviewers use this field sparingly. I might write comments in this field such as “I reviewed the first part of the manuscript, but lack the expertise to evaluate the second part. I hope you were able to get a reviewer with expertise in that topic.” Or, “Professor Williams did prior work on a very similar topic–it may be helpful to get her opinion on whether this work adds significantly to the field.” Or, “I previously reviewed this manuscript for Journal XX, and recommended rejection. I repeated my review here as the authors did not revise the manuscript since that rejection.”

The Associate Editor will synthesize the reviews and decide what to do. If several reviewers provide convincing reasons to reject the manuscript, the Associate Editor will likely recommend rejecting the manuscript. If the review comments indicate that with some adjustments the manuscript could be publishable, the Associate Editor will usually recommend that the authors revise and resubmit it for further review. Some journals will distinguish between minor revisions needed and major revisions needed to indicate whether they expect to see superficial or more significant changes in a resubmission. It is extremely rare for a manuscript to be accepted after an initial review by a competitive journal–even the best manuscripts have a few items that could be improved.

The Associate Editor will recommend a decision to the Editor, along with a synopsis of the reviews and support for the recommendation. In most cases, the Editor will agree with the Associate Editor and return the reviews and synopsis to the author.

The Editor will be named in the correspondence you get from the journal, but the reviewers are usuallyu anonymous. When the authors are known to the reviewers, but not vice-versa, the process is called “single-blind.” A few journals use “double-blind” review, where the author names are removed from the article, and neither the authors nor reviewers are known to each other. There are also emerging forms of “open peer review” processes. But single-blind reviews are typical in most fields.

Decision

Once a decision has been rendered, you will get a letter like the following.

Dear [you],

Your manuscript has been reviewed. The comments of the referees are included at the bottom of this letter.

Your manuscript is recommended for rejection/acceptance/revise-and-resubmit.

[instructions on what to do next…]

[lists of review comments]

Sincerely,

[The Editor]

If you are rejected, your interaction with the journal is complete. Take the reviews to heart and make changes before you consider resubmitting to another journal. Sometimes, a rejection is erroneous, and your work is publishable as-is, but get an independent evaluation if you think this is the case. You are better off taking time to publish an improved paper than by trying to cram a flawed paper through at another journal.

I have had manuscripts rejected a few times. My most disappointing rejection came when I was a graduate student and still calibrating how valuable my contributions were. Fortunately, my advisor counseled me that the decision was inappropriate, and we published it elsewhere with minor edits. In a few other cases, reviewers have rejected my manuscripts due to deficiencies that we hadn’t identified or hadn’t had the persistence to fully resolve. In those cases, I was careful to improve the work if we decided to resubmit elsewhere.

Revise and resubmit

If you are asked to revise and resubmit, you will get a detailed list of comments from reviewers. You will need to respond to these when you resubmit, by revising your manuscript and documenting what you have changed. See this article for advice on preparing your revisions.

You will resubmit your revised materials through the same web portal as you used for the initial submission. Typical items to submit at this stage are:

A cover letter. This could be the same as before, but you could comment on the reviews or your response if anything is unusual.

The “response to reviews” document.

Your revised manuscript.

Sometimes, a copy of the revised manuscript with changes showing so that reviewers can easily see what is new in this version. The latexdiff package [https://ctan.org/pkg/latexdiff] is useful for this if you wrote your manuscript in Latex.

The Editor will send your materials back to the Associate Editor who handled the initial review. The Associate Editor may make a recommendation on their own if they think the outcome is clear, or they may send your materials back to reviewers for further comment. Usually, the same reviewers are used, as they are best equipped to evaluate responses to their previous comments.

The manuscript might still be rejected if it does not resolve initial concerns, and there seems to be no clear path to a publishable version. Or it may be accepted if it has reasonably addressed the comments. Or there may still be unresolved issues that the journal asks you to further address in another round of revisions. The journal will usually try to get to a final decision within two or three rounds of reviews, but there is no strict limit on the number of review cycles before a final decision is rendered.

Post-acceptance processing

When the journal accepts your manuscript, you will get a message noting this decision and explaining what to do next. You will be asked to submit your final materials, including the following:

The final version of your text, in Latex or Word format, so that the typesetter can edit it.

High-resolution image files for each figure.

The signed copyright form (if you didn’t submit it earlier).

You can make no further changes after this submission, so make sure that you are happy with everything when you upload it.

A typesetter will next prepare “proofs” of the final document, with everything laid out and formatted as it will look in the final published version. They will send the proofs to you for review. They may also send some questions for you to answer (e.g., confirming whether they have correctly listed information for some references). You will need to answer their questions and review the entire document to check that they haven’t introduced any errors. Symbols, acronyms, equations, and figures are common places for errors to arise, so check those parts carefully. You can provide a list of corrections if they introduce errors, but don’t make further changes to your own writing.

After the proofs are finalized, the journal may post the paper online. If it has a final DOI assigned to it, it is considered “published” at that point. The journal may also include it later in a print issue (giving it a volume and page number). That used to be important when issues were mailed out, but now the online posting essentially finalizes the process.

How long will this process take?

The review process can feel slow, but consider the steps it took to get to this point. The journal and Editor may take a week or two to do an initial review and assign it to an Associate Editor. The Associate Editor may take a week or two to invite reviewers. The reviewers may take a few days to a week to accept the invitation, and then a few weeks or months to complete their review.

It may take one to three months for you to get your review comments back after submitting, and you will need perhaps one month to revise your manuscript and resubmit. Then it will take a few weeks to months for the revised submission to be processed, depending upon whether the Editor sends the manuscript back to the original reviewers. Post-acceptance, typesetting and final publication often take one to three months.

Overall, 6-10 months from submission to publication is common in my experience. Many papers have a note on the first page listing the dates when the paper was submitted and when it was published–looking those can give you a sense of how fast a particular journal is.

Taking credit for your paper

Depending upon the stage that your paper is at in the process, you can cite it in your CV in one of the following ways:

Baker, J.W. (2021) “My paper’s title,” Journal Title, Volume 37, Issue 3, p 312-325.

Baker, J.W. (2021) “My paper’s title,” Journal Title, (in press).

Baker, J.W. (2021) “My paper’s title,” (in review).

Baker, J.W. (2021) “My paper’s title,” (in preparation).

Case 1 is for after the paper has been published. Case 2 is for after the paper has been accepted, but before it has been published. Case 3 is for after you submission but before acceptance. And Case 4 is for when you are working on the manuscript and haven’t submitted yet. If you create a preprint, include the preprint DOI in the citation for cases 2 and 3, and use the journal’s final DOI in case 1.

Young scholars are often concerned about listing publications on their CV. Cases 1 and 2 count for similar academic “credit,” as they both demonstrate that your scholarship passed through the peer-review process. Case 3 is less valuable–it indicates that you completed a manuscript, but does not yet demonstrate that the work is of high quality. Case 4 is worth very little–it provides no evidence about the degree of completion or quality of the work.

If you list in-review manuscripts on your CV, leave off the journal title. The journal hasn’t evaluated whether they will accept it, so you don’t yet have the right to associate its name with your work (one exception might be if you submitted to very competitive journal, and have survived the desk rejection stage and proceeded to formal review). Listing speculative journal titles can also be slightly embarrassing if you eventually publish the work elsewhere because of an initial rejection.

Closing advice

First, be patient. The above process is time-consuming, and you will spend a lot of time waiting. You can help a little by moving your parts of the process along quickly. A one-month delay in submitting your manuscript or responding to comments has the same impact as a one-month delay in getting review comments, but you have control over the former.

Second, volunteer to review manuscripts so that you can learn about the process from the other side. This experience will be eye-opening in helping you see what makes a paper readable and how the reviewing parties interact with each other to get to a decision. If you ask, your advisor may recommend you to some Editors, or if they are an Editor they can assign you manuscripts directly. The journal will probably be happy to have your help, and the experience should make you a better writer.

Finally, really celebrate when your paper is accepted! You have put hundreds of hours of work into the project by this point, and publishing a paper is a special occasion even for experienced scholars. Savor the accomplishment of successfully contributing to a system that has advanced scholarly research for centuries.

Sign up for very occasional updates about new offerings.